Lucy Terry Prince

Topics & Ideas

WIREFRAME ONLY - NOT YET DESIGNED

Topics and Ideas

Marriage in Early New England

About

Matrimony and setting up one’s own household were cultural aspirations for both men and women in early New England. Courtship and marriage occurred in a hierarchical society in which the male head of every household was held responsible for the physical and spiritual well-being of his wife, children, apprentices and servants, including enslaved men, women, and children. In return, every member of that household owed loyalty and obedience to the head of the household, who possessed a legal right to use physical force to attain or ensure compliance.

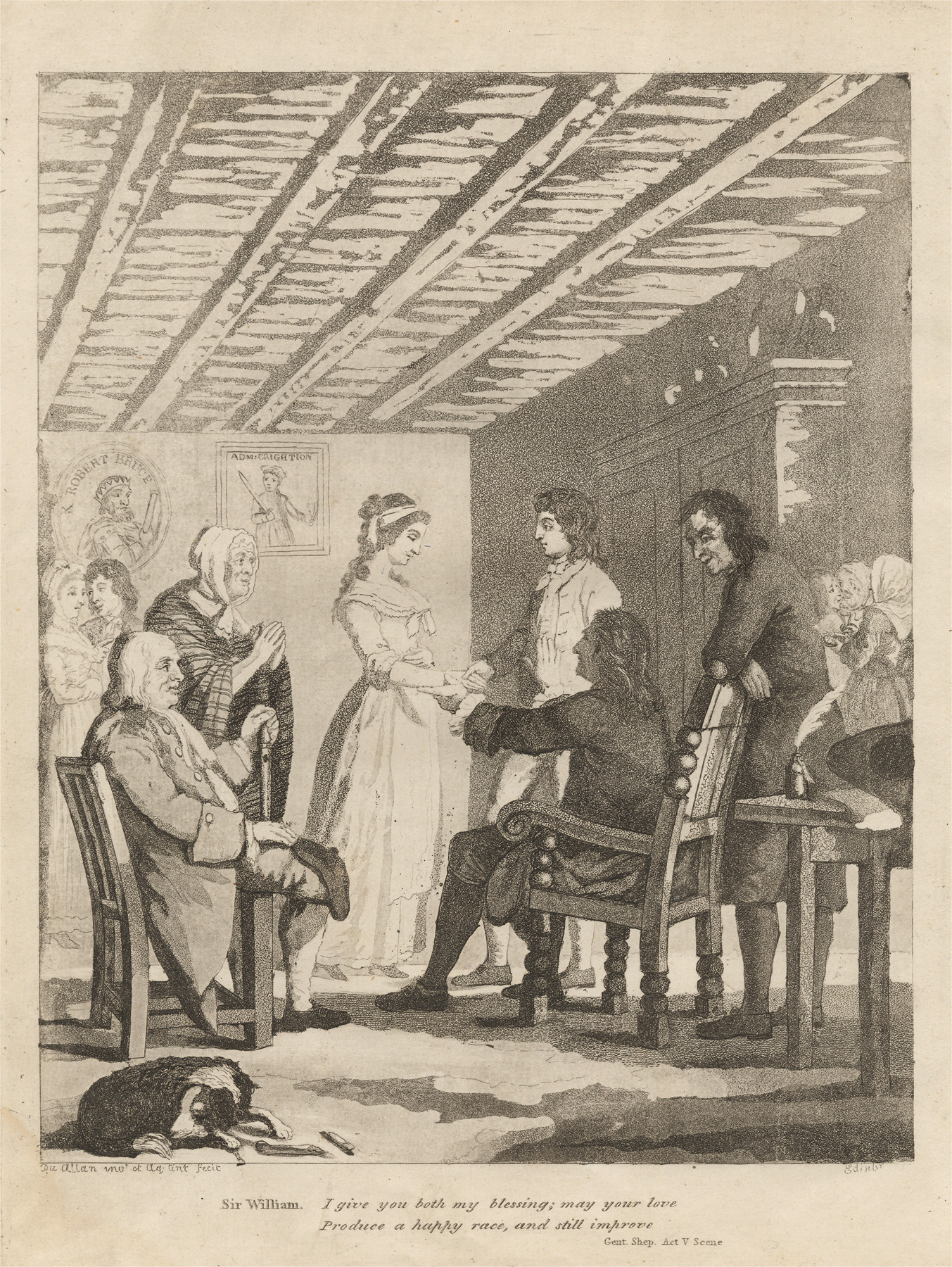

The head of a household had the power to allow or forbid marriage by those under his control for any reason. In 18th-century New England, a father had a legal right to forbid a child’s marriage; patriarchs could also withhold inheritances from children who wed against their parents' wishes. A man wishing to marry a woman had to gain permission from the man who supported her in his home—typically a father, stepfather, uncle, or brother or in the case of an enslaved woman, her enslaver. The present-day custom of a hopeful suitor asking a father for permission to wed a daughter is a cultural vestige of the power once held by the patriarch to permit or forbid a marriage from taking place. In cases where permission was granted, the couple had to legally notify the community of their intention to marry by publishing banns, an official announcement identifying both the prospective bride and groom on three consecutive weeks. In many towns, the banns were read at the end of a church service. Such an announcement was intended to prevent clandestine marriages and also enabled those familiar with the couple to raise potential issues such as an already-existing marriage or claims of consanguinity. It also offered opportunities for community members to congratulate the couple and celebrate their union.

In such a society, the power of an enslaver to allow or deny permission for an enslaved man or woman under their control was absolute. There were also financial hurdles, as men wishing to marry an enslaved woman might negotiate the terms by which they could purchase a prospective spouse. If successful, such a marriage became a pathway to freedom for a woman. Crucially, any children born to her once she was emancipated would inherit her free status. Examples of emancipation as part of marriage include Venture Smith of Connecticut who purchased his wife’s freedom, and Amos Fortune of Woburn who purchased the freedom of his first and second wife. It is possible that Abijah Prince of Deerfield, Massachusetts, may have negotiated freedom for Lucy Terry before they married. Although no extant evidence has yet been found to support this theory, it is a likely scenario, as town records record their marriage by a Justice of the Peace and all six of their children were born free. Thanks to surviving church records, we know that Lucy and Abijah’s first child, Caesar Prince, was born on February 13, 1757—nine months after his parents were married.

Premarital sex was more or less tolerated so long as the couple married. The situation was far more serious when the expected marriage did not or could not take place. The unwed mother was shamed. The couple’s illegitimate child was a charge to the town unless the father (identified by law by the mother while in labor) could be forced to pay child support. It was no wonder that most early pregnancies resulted in the couple’s marriage sooner or later.

At the same time, cultural pressure on a courting couple to delay their union until they were able to set up their own household delayed most men from marrying until their mid-twenties, while women tended to marry in their early twenties. For enslaved men especially, establishing an independent household with the ability to support a family was unattainable without first emancipating themselves. Such an outcome was out of reach for most, and even those who were able to surmount that challenge typically devoted painstaking resources accumulated over many years. This helps explain why Amos Fortune, for example, had to delay marrying until his early 60s. Similarly, Abijah Prince was 49 when he married Lucy Terry in 1756, five years after he gained his freedom.